As Black History Month comes to close, we’re taking a look at Eugene’s own exclusions and later achievements through the eyes of some of the Black community’s elders.

When Oregon became the 33rd state in 1859, it was the only one with exclusionary laws still in place.

In the ’20s, the Ku Klux Klan was a strong force in the state and in Eugene.

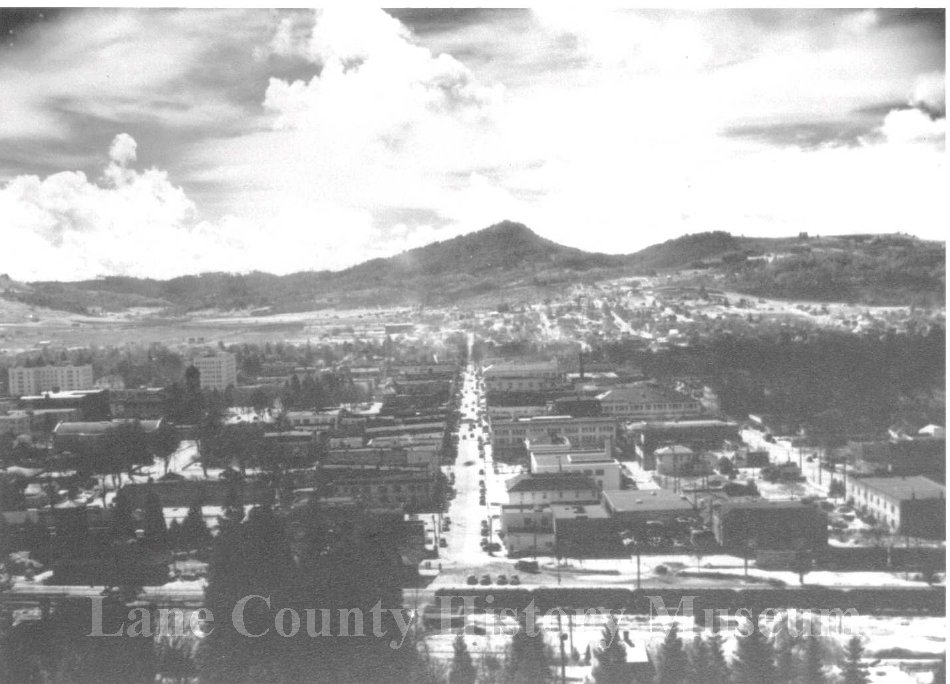

In the ’40s black families couldn’t live in Eugene.Volume 90% KVAL

The Mims family were one of the first Black families here.

Their houses were a family home and a safe haven.

We also spoke to a University of Oregon graduate who hardly left campus because of racism.

“It was segregated,” explains Ben Johnson, who attended the University of Oregon in 1949. “We knew that in Eugene. You just knew. Apparently, someone tried to go [to a restaurant, etc.], were refused, and the word gets around.”

Johnson was an athlete – one of just 12 Black students in total.

Johnson says the town wasn’t welcoming so they stayed on campus.

Today, the Mims properties on High Street house the local NAACP office.

The Mims bought the property in 1948 under the name of C.B’s sympathetic white employer because Black families weren’t allowed to buy in Eugene in the ’40s.

“This was really a central point for the Black community in many ways,” says Eric Richardson with NAACP.

C.B and Annie Mims had two children – a daughter, Pearlie Mae, and a son, Willie.

“He was one of the original crew of kids who were over at the village ‘across the river,’” says Richardson.

They had no running water or electricity.

Ferry Street Village, “Tent City,” or known to residents as “across the river,” it was the first Black neighborhood the county demolished back in 1949 to make room for Ferry Street Bridge.

Lane County Commissioner Joe Berney says they gave no notice to residents and two-thirds of those residents were Black.

Earlier this month, Lane County adopted an order and resolution to acknowledge the destruction, the racism, and to honor the history of the Ferry Street Village with plans for a memorial at Alton Baker Park.

Willie Mims, at a City Club of Eugene meeting in 2016, spoke on the Black experience in Eugene.

“If you walked with me in downtown Eugene back then – in the mid ’40s – you would have seen racist signs displayed in plain view,” Mims said. “When there were no signs, the attitude they represented was present throughout the entire community.”

“African Americans at the time were not welcome in the local hotels and whatnot,” says Richardson. “So the family, through word of mouth, would board people.”

Those they helped included musicians Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, and Ella Fitzgerald, and Black athletes at the University of Oregon.

Richardson says Willie was pivotal in the ’60s, during the civil rights movement.

“He helped bring about the idea of bringing the Black Panthers to town,” says Richardson. “He was friends and corresponding with those folks.”

He was also part of local social justice work like the Congress for Racial Equality.

When asked about his hope for a better future,” Mims said, “I have a lot of hope simply because – it can only go up.”

And he said work must be done on each issue at a time.

“By being active, listening and becoming a part of the energy is the only way we’re going to lift the boat,” said Mims. “And I think it takes all of us to lift the boat.”